Creating Positive School Environments: Perspectives on the Impact of Leadership Development from Kentucky Principals

In 2015, Truist Leadership Institute (TLI) began making a difference in Kentucky communities by offering principals leadership development programs. These programs have positively impacted the principals and the teachers, staff, students, and parents they serve.

The program, called Leadership Institute for School Principals (LISP), offers public and private school principals in Kentucky an opportunity to receive powerful individual leadership training. The Kentucky Chamber Foundation sponsors the LISP program in partnership with the Truist Leadership Institute. Over 500 principals from 104 counties have participated in this program since its inception!

Participating principals go through a series of TLI programs that focus on building organizational engagement, navigating change, and crafting self-awareness about how principals show up as leaders. One part of the program includes an immersive 4-day experience. Principals stay at TLI’s beautiful campus in Greensboro, NC, allowing them the solitude and space to truly focus on their individual leadership development.

The TLI research team conducts evaluations to understand the impact TLI’s work for all our leadership development programs. In addition to our own impact tracking, participants sometimes send us deeper feedback that describes the immediate and profound changes they experience after attending TLI programs. This was the case for the LISP program.

Six Kentucky principals from Henderson County voluntarily sent TLI letters detailing their experiences and the subsequent changes they made as school leaders. Below, we summarize our new understanding of how we’ve impacted these principals’ careers (and, in some cases, their lives beyond the school) and how research affirms that our programs can make a difference. First, we’ll set the scene regarding what principals face in their daily work.

A Typical Day for a Principal

A typical day for principals is chaotic. After ensuring students have a meal in the morning, a principal might de-escalate a fight that broke out on a bus before checking classrooms to see if a substitute teacher didn’t show. It isn’t even 8 AM yet. When the principal goes to settle into their office, parents and staff will already be standing in line to have their own concerns addressed. Afterward, the principal’s attention is split between policy and regulation updates, endless paperwork, and reporting. Once students leave, the principal’s workday continues for several more hours with parent-teacher meetings. The next day, they do it all over again.

Principals face a packed schedule, teacher shortages, and bus drivers calling out sick, making it difficult to provide students with essential services. Everyone’s expectations for principals to keep students safe are constantly mounting—and that’s on top of demands to ensure students perform well on end-of-year tests.

These are the stakes principals face—and why it’s so important for them to exhibit excellent leadership while pacing themselves under immense pressure and scrutiny.

The Impact of Our Programs According to Kentucky Principals in Henderson County

Principals face complicated work. TLI programs help leaders address this complex work by beginning with self-awareness and developing balance. Leaders look in a metaphorical mirror to understand how they show up. They learn how their beliefs affect their behaviors—and by extension, how their behaviors influence other people’s reactions. Nothing in a school’s ecosystem exists in isolation. Everything is connected, including the many relationships principals must balance: With administrators, students, teachers, and parents. Principals’ ability to lead through complex issues across the many competing needs of these complex relationships begins with self-awareness.

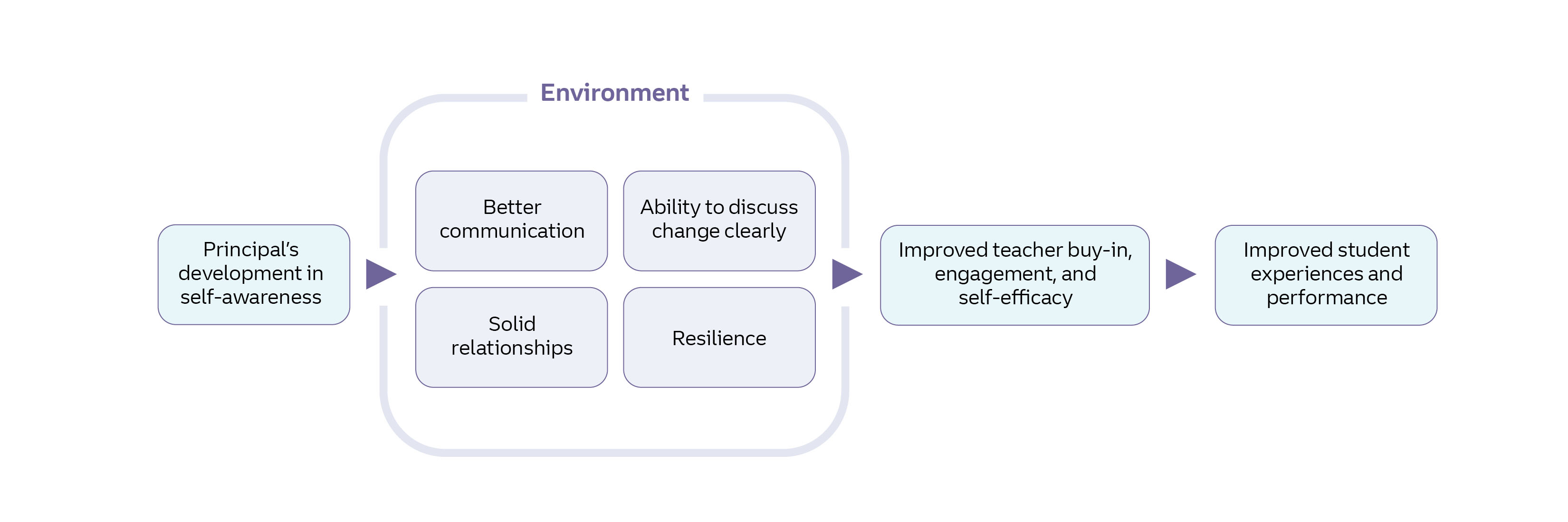

The Henderson County principals’ letters shared with TLI illustrated how their new self-awareness benefited their work. Their descriptions of our programs’ impact are captured in the theoretical model below, reflecting the changes experienced by the principals themselves, the environments they created, and impacts to teachers and students.

The theoretical model illustrates the key points from principal’s letters but has not been statistically validated given the qualitative nature of the letters. The letters also reflect the experiences of a limited group of principals from a single county in Kentucky.

Be the Leader You’re Capable of Becoming

Truist Leadership Institute believes that anyone can be a leader. Anyone can learn how to lead in a way that creates positive results if they commit to change by changing their beliefs and behaviors. When principals leave TLI programs, they have often changed their mindsets and have new tools to apply when they return to their school environments.

Principals who leave our programs can use these tools to improve their school environments. They are relevant across time and situations—exemplified by principals saying that our program helped them show up stronger in both their personal lives as well as their roles as principals. When leaders use these tools, they gain the ability to better understand themselves and their teams. This new understanding modifies how leaders view situations and provides new skills for effective behavior and team relationships.

Development in self-awareness clarifies biases and blind spots that may hold leaders back. When we equip leaders with these tools and mindsets, we don’t change who the individual is—rather, we help individuals enter the stretch zone so they can imagine who they’re capable of becoming (Ibarra, 2015). One principal noted they moved from a focus on leadership style to a focus on strategy. According to the book, Mindset: The New Psychology of Success, this type of change would allow them to let go of self-limiting beliefs about style and imagine how they could develop new skills (Dweck, 2006). This is profound change given the prevalence of the idea that leadership is something that you either have or don’t (see Flink and Coley, 2024 for a research-based counterargument to this idea).

Effective Change Communication: Personalizing the message about WHY

Schools undergo constant change driven by political environments, funding, policy work, and even shifting community demographics. When change happens, how does a school stay on-course and keep focused on its students? A lot depends on the connections between principals and their school administrators and teachers. Positive connections can foster clear and quick communication. Negative connections can create difficult rifts.

Many letters discussed the importance of communicating with stakeholders about why something is happening—especially in school environments that are rife with change. Importantly, principals must be able to communicate about change that they themselves created and change that they did not have a hand in because it came from the district, state, or federal level. In either situation, principals must create buy-in. One principal described their improved communication style this way:

“Through the program, I learned about different leadership styles and how to adapt my style to fit the needs of my school community. This allowed me to lead, manage, and assist others through the inevitable changes in education and the daily changes within my school.

With effective communication and having greater self-awareness and knowledge of change preferences, I was able to effectively lead my staff through all the changes of moving into [a new school] and through the changes and challenges of leading a school through the pandemic in 2020.”

Influencing others to adapt to change can be challenging. One principal said, “it’s personal.” People want to first understand who’s involved in a change and why. Afterward, they are receptive to the “what and how.” Our programs teach that getting this out of order—describing the change then backtracking to explain why it’s happening—can undermine people’s autonomy and make them more resistant to change (Galbraith, 2018). Another principal affirmed the importance of explaining “why” to stakeholders:

“I began telling the ‘why’ behind decisions made, and I saw so much improvement. I still use it to this day. When things seem off, I can always go back to—I forgot to tell the ‘why.’ I know what to do when data is not in our favor as an individual and as a school.”

Even though people vary in their change styles, everyone wants to know the “why” behind decisions. Understanding this is invaluable for creating buy-in. It requires patience, a listening ear, and a willingness to expand one’s perspective. Principals get to do that during our programs by collaborating with, and hearing ideas from, principals at other schools—reinforcing that there is no singular way to go about things.

Seeing with New Eyes: The School as Interconnected Parts to Foster Success

In our programs, principals from Henderson County saw their schools as an integrated system and recognized new levers they could pull to enhance outcomes at their school. They adopted a systems perspective, understanding that no aspect of the school is isolated. Improving one aspect of the system can improve other aspects downstream (Shaked & Schechter, 2013).

For example—better student achievement is an outcome that’s influenced by the environment—including a positive work environment, which enables teacher buy-in, improves retention (Jerrim, 2024) and fosters higher self-efficacy (Mehdinezhad & Mansouri, 2016). According to the principals’ letters, the positive environments they built were based on better connections and communication, enhanced resilience, and treating conflict as something that leads to insights instead of something to be feared.

One principal brought this example to life by describing their success with a specific problem:

“Our scores were stagnant. We had made little to no progress, even though our team was working hard every day. The process taught me to deeply analyze and understand this problem, enlist key stakeholders (core team) who would be instrumental in this change, build a vision, and a common goal, and ultimately develop a strategy for how to achieve excellence.

Our team set a goal to reach this level of academic excellence and committed to the ‘change process.’ We worked together to build effective systems to improve student achievement.”

This principal recognized the power of their school’s culture. As principals foster collaboration, buy-in, and the sharing of feedback and ideas, it changes the atmosphere. Their schools become a better place to work. This allows teachers and administrative staff to use their talents productively so they can fully engage in their roles (Christian et al., 2011).

Improving Student Outcomes: Ascending Performance and Reinforcing Purpose

Principals said that their experience with our programs led to improved student outcomes. The superintendent of Henderson County schools commented on these patterns:

“There is a significant difference in the amount of growth in schools led by alumni of Truist Leadership Institute. The growth in schools led by Truist scholars far exceeds those who have not completed the program. We have also seen noteworthy achievement increases in schools when looking at pre-Leadership Institute versus post-Leadership Institute participation. This is not an anomaly. It is a testament to the valuable programming, curriculum, and experience our leaders have had during this institute.”

The superintendent’s observations are supported by the data shared in these letters—including an increased number of students achieving a “Proficient” or “Distinguished” score in Reading or Math (in 2023, there were 1.2 – 3.0 times more students with these designations compared to 2021). Many principals’ schools received awards and higher ratings from the state of Kentucky for excellent student performance. These achievements included the TELL Kentucky Survey Winner’s Circle Award and a National Blue Ribbon School recognition. These results highlight the impact of principals’ commitment to leadership on student achievement.

Principals’ shifts in their own self-awareness and leadership behaviors created more positive environments for their schools. Relationships improved with key stakeholders, including administrators, students, parents, and staff. Improved outcomes for students’ success may have reinforced principals’ views of the purposefulness of their work, emphasizing that they can make a difference and making them even more resilient because they knew their efforts would be worthwhile (Hill et al., 2016).

Looking to the Future

These principals’ letters demonstrate that enhancing the leadership of just one person in the building can snowball into more positive school environments and better student outcomes. Great leaders inspire others to strive in their own roles and to mindfully steer through change and turbulence.

School principals hold enormous responsibilities: The care and safety of students and staff, achieving academic excellence, building teams, and the management of stakeholders who often have differing viewpoints. Their days are frenetic, characterized by disruptions, competing priorities, and sometimes high emotions. However, as principals achieve positive outcomes through their actions, situations that could have ended in chaos will instead result in satisfaction and reward. This allows teams to develop students to where they need to be—safe, reassured and focused on a bright future.

These outcomes all begin with one step—a central leader looking inward and believing that the time invested in themselves will grow the connections they have with the people they rely on.

Related resources

Creating positive school environments | Truist Leadership Institute

Philanthropy & education

Creating Positive School Environments

Six school principals in Kentucky share new perspectives on the impact of leadership development programs designed to create positive school environments.

Six school principals in Kentucky share new perspectives on the impact of leadership development programs designed to create positive school environments.

Be true to your schooling | Truist Leadership Institute

Philanthropy & education

Be true to your schooling

A former student and a team of educators share how Truist Leadership Institute’s programs elevated their leadership style.

Discover how Truist Leadership Institute's programs empower educators and students to understand their leadership styles, enhance decision-making, and build cohesive teams.

{3}

Interested in learning more?

Contact us, subscribe to our newsletter, or follow us on LinkedIn to keep the conversation going.

Connect with a Business Advisor

One of our seasoned Business Advisors can guide you through our range of offerings and help you select the best options for you, your team, or your whole organization.